Cooking with Artificial Ingredients

Published:

Sometimes meandering through the labyrinth of life is monotonous and in desperate need of being spiced up. However, this just leads us back to the age old question: what spices should I use?

Many merchants traversed the globe in search of an answer (and insect larvae waste). Thanks to their trade and centuries of cooking and gastronomy research we have developed a methodic, proven system for the culinary arts. However, we are almost a year into covid-times and the world just does not make sense anymore, so why should my cooking? Thus, I present an unnecessary, over-the-top recipe generator using machine learning. And, sure, this may seem neat, but just ask your average Byzantine which is cooler: a neural network or my spice cabinet.

So how does one create recipes with machine learning? For once googling keywords was no help as ML researchers have taken to the practice of typing up their messy notes and calling them ‘X Cookbook’ where X is some generic data science jargon. Leading me, on an empty stomach, to have to actually think a little.

Design

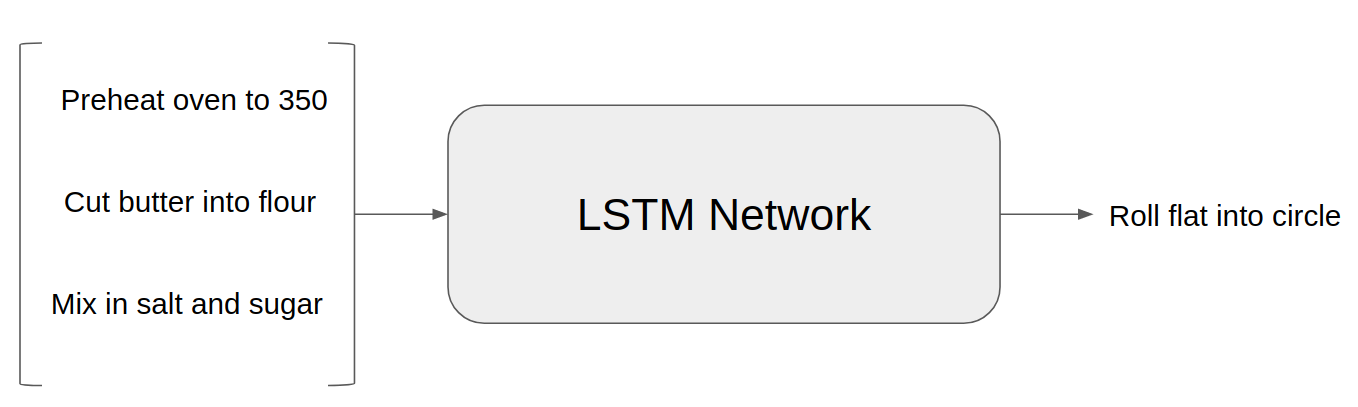

First, a naive approach with no domain awareness, i.e. this method will not leverage any specific knowledge about recipes except for their ordering. Recipes are sequential data: a list of unordered ingredients and ordered steps to completion (note: I am ignoring the life stories which typically precede online recipes; generating these is left as an exercise to the reader). Thus, some classification technique with memory should do a decent job. Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) neural networks have become a standard for this type of classification task.

LSTMs, in their typical use case, take an input sequence and predict the next item in the sequence. An example could be forecasting temperature data for tomorrow given the previous 10 days. This “memory” of the previous couple days is how LSTMs differ from traditional neural networks. Rather than learning from a single static point they “remember” the previous inputs and utilize this information in their predictions. While this makes LSTMs seem more powerful than traditional networks, they still require temporal input data and struggle to learn from multi-dimensional input spaces.

Of course, existing data are needed to train the model on how to predict new samples. In our case these data are recipes. Luckily the internet is plump with well-formatted recipes making it easy to scrape them with a simple Python script1. There is also an existing dataset curated by Majumder, et al [1], but it seems to focus more on user comments than recipe contents.

Experiment

First, I will try the naive approach as it should not be too hard to implement2. I used a collection of recipes as my training data with the ingredient list and recipe steps parsed apart. In designing my dataset I faced the important decision whether to preserve the individual recipe dimension, i.e. should I keep all recipes separate in the dataset or join them all together. Keeping them separate would require either adding an extra dimension or padding/truncating recipes to all have the same length. LSTMs require significant amounts of data to train with added dimensions (and it is slow) and my recipes varied significantly in length so I did not want to pad them all to the same size. So I decided to join all the recipes together into one giant super recipe and place unique tokens in between them. Now the data looks like

\[[ \textrm{Ingredient 0}, \textrm{Ingredient 1}, \textrm{Ingredient 2}, END\_INGR,\\ \textrm{Step 0}, \textrm{Step 1}, \textrm{Step 2}, \textrm{Step 3}, END\_STEP, \textrm{Ingredient 0}, \ldots ]\]As ML models require numerical values to learn I assigned each ingredient and step a unique integer and transformed the dataset using this mapping. See below for an example.

\[\begin{bmatrix} \textrm{Ingredient 0} \\ \textrm{Ingredient 1} \\ \textrm{Ingredient 2} \\ END\_INGR \\ \textrm{Step 0} \\ \vdots \end{bmatrix} \mapsto \begin{bmatrix} 829 \\ 39 \\ 432 \\ 1 \\ 91 \\ \vdots \end{bmatrix}\]Ding! The data is ready and now we can move on to designing the learning mechanism. As I mentioned an LSTM should perform well on this task. For this approach I am just going to use a standard LSTM setup with 512 units. The network architecture is

\[\textrm{Embedding} \rightarrow \textrm{LSTM} \rightarrow \textrm{Dropout} \rightarrow \textrm{Dense}\]I implemented everything in TensorFlow 2 and Python 3. You can find the source code here. Since the network is actually quite large I hoped to train it on my desktop with a GPU, but Windows decided it was a good weekend to corrupt its own partition on my hard drive. That or it was scared of my recipes. Thankfully my laptop kindly allowed me to abuse its CPU for a couple days. The network took ~45 minutes per epoch when I lowered the vocabulary size to 15,000 unique values. Both my compute limitations and lack of patience kept me from running for more than 10 epochs.

Results and Dinner

To get a random recipe from the LSTM you can feed into it an initial random ingredient and read the predicted next item. Then you append this item to your input sequence and feed it back into the network. This can be repeated until you have a sequence of desired length or in our case until the network outputs the unique ID for \(END\_STEP\). Now we can use our data mapping from before to translate the numbers into ingredients/steps and voila!

Now what is the point of any of this if I am not going to use it? So let me put my money where my mouth is… Or my mouth where my neural network is and try preparing and eating an artificially generated recipe. Besides, this whole time I have had a BuzzFeed-esque article title in my head: Letting AI Tell Me What To Eat.

I wanted to choose one of the first couple recipes that came out rather than just wait around for something that sounded good. Several of the first ones just did not make practical sense or they were a list of ingredients and just said to preheat the oven. Some of these first recipes also led me to believe my CPU was mad at me for pushing it to its limits, because it kept recommending meals with uncooked meat. But after a handful of recipes popped out I found one that seemed possible to make and, much to my surprise, actually sounded good.

| Ingredients | Steps |

|---|---|

| italian sausage elbow macaroni water olive oil cooked brown rice | cook meat until brown cook pasta according to package directions turn onto a floured surface add salt and pepper to taste |

I am going to interpret the turn in “turn onto a floured surface” as mixing the ingredients all together on my counter top (with flour of course) even though I do not think that is what it means.

And… It is not terrible! The concoction is in desperate need of some sauce or maybe more spices. I probably deserved just salt+pepper though for my corny opening to this post. However, it is also not bad. I made sweet italian sausage, which has a lot of flavor to it and helps the bland rice+macaroni mixture. I could do without the counter top flour though.

Improvements and Next Steps

The naive approach actually turned out pretty great considering my only two goals were to improve on a blindfolded trip to the supermarket and be less profane than Gordon Ramsey. In fact, the LSTM was still improving in terms of training accuracy and loss at 10 epochs, so I believe more computational resources could ameliorate the network’s performance. Perhaps I could sell cookbooks for money to buy better GPUs.

Yet an even better approach would be something which is aware of the relationship between recipe steps and ingredients. Consider this example recipe step: “Cut the butter into the flour”. Here butter and flour are ingredients which should be in the associated ingredients list. A smarter system should be aware of this syntax and its underlying meaning as well as learn how to generate it. A model which does this would be much more complicated than what I implemented, but it could theoretically produce more consistent results.

In its current state the algorithm is still a couple notches shy of a Michelin star. So what is the point? At first the effort was just a boneheaded attempt to entertain myself, but I think the idea has a couple promising directions in terms of applicability. One of these being a recipe auto-complete tool. Since the LSTM takes a sequence to begin, then you do not have generate an entire recipe, but can start in the middle. Maybe you have a really tasty way to cook chicken, but are looking for some ways to add to the recipe. Or maybe you need to finish off those leftovers, but you would like to spice them up a little. The possibilities are endless.

Honorable Mentions

For the time being I only cooked one recipe, but here are some of my favorites. They are not necessarily sensible recipes, but funny nonetheless.

| Ingredients | Steps |

|---|---|

| chicken breasts smooth peanut butter | cool bake at 450 degrees for 15 minutes remove meat from marinade |

I am really disappointed I did not end up getting this one first. I have always thought chicken breasts need a little more peanut butter. It also seems a little bit out of order.

| Ingredients | Steps |

|---|---|

| milk egg yolks vanilla butter milk | set aside, and keep warm |

Ah yes, my favorite blend of ingredients at room temperature.

| Ingredients | Steps |

|---|---|

| powdered fruit pectin vanilla extract zucchini water | preheat oven to 325 cook transfer to a large bowl cool |

Maybe an actual tasty Zucchini snack? Cannot be sure until I try it.

| Ingredients | Steps |

|---|---|

| wheat bran oat bran brown sugar unsweetened applesauce vanilla instant pudding mix milk salt boneless skinless chicken breasts flour | heat oven to 350 add garlic cook for 1 minute more |

I am glad the AI decided to include brown sugar to sweeten the applesauce here. Not sure where the garlic comes from though.

| Ingredients | Steps |

|---|---|

| russet potato |

Instructions unclear. Made vodka by mistake.

Footnotes

1 After heavy use of the BeautifulSoup library for web-scraping I am now quite fond of the Adjective+Food naming convention. My next software project will be called DomineeringPickle followed by AdventurousBaguette. ↩

2 The only thing naive about this approach is me saying it would be easy to implement. ↩