The Digital Librarian

Published:

I love scouring old book stores for cool finds and oddities, but I often worry about missing a diamond in the rough. Unfortunately, there is not enough time to dive into every book in a shop and if we cannot judge a book by its cover, then how are we supposed to judge them by only the spine! As a true computer scientist I decided to build an over-the-top tool to help me out.

After some lengthy research into computer vision I built an app, which allows you to point your phone camera at a bookshelf and see information about each one of the books in front of you. Unfortunately, text-detection and OCR within a scene are non-trivial tasks and I was only able to get around 70% accuracy rate on identifying books. But this number is also skewed by the fact that a lot of old books in used book stores are crumbly and hard to read with even a human eye. Improving this accuracy rate is saved for a later date. The tool also turns out to be great for cataloging your own bookshelves at home!

Algorithm

A Line of Books

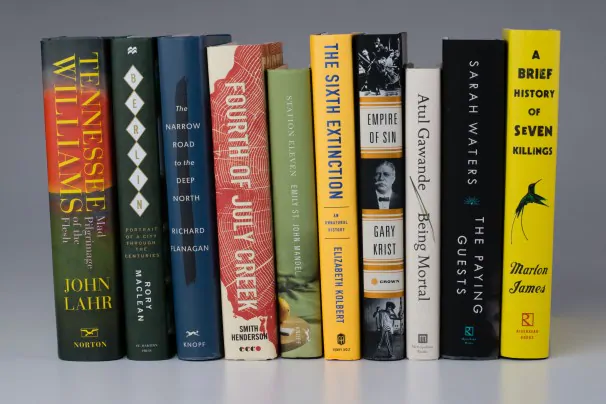

For the rest of this post I will use the below image from this Washington Post article as an example image.

In this image we have 10 books lined up next to each other. Simpler images can often be segmented (split into objects) by finding edges and then finding contours. This simpler approach, unfortunately, does not work for bookshelves very well as the books are “connected” making it hard to find a good contour. So we need something a little more clever.

Picking Books

The first thing we need to do is identify individual books within the image and divide them out. To do this I am going to use a technique called the Hough transform to identify lines within the image.

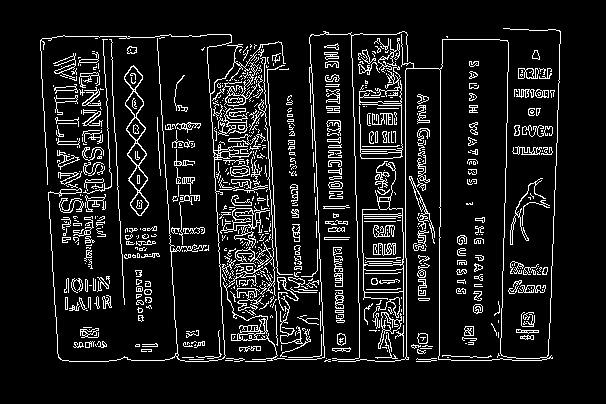

However, we need some preprocessing steps before using the Hough transform. First, we need the edges of the image. To do this we must first convert the image from 3 channels (Red, Green, Blue) to 1 (Grayscale). Once in grayscale Canny edge detection can pull out the edges [1].

Canny edge detection works by first applying the Sobel operator to get gradients in the \(x\) and \(y\) directions, \(G_x\) and \(G_y\). Then, for each pixel we can use the below equations to calculate the edge gradient and direction.

\[Edge\_Detection(G) = \sqrt{G_x^2 + G_y^2}\] \[Angle(\theta) = \arctan\left(\frac{G_y}{G_x}\right)\]Now we “suppress non-maximums”. This is fancy speak for looking at each pixel and determining if it is a local maximum in the direction perpendicular to the edge. The calculated gradients give us the perpendicular edge.

Finally, we examine each edge pixel from above and check whether it is really an edge using low and high thresholds. Below the low threshold and it is not an edge. Above the threshold and it is definitely an edge. In the middle and it is only an edge it is connected to another above or in-the-middle pixel.

After these steps we should have pretty good edges for our image. This page has a much better explanation of Canny image detection with pictures. See the below image for the books with Canny image detection.

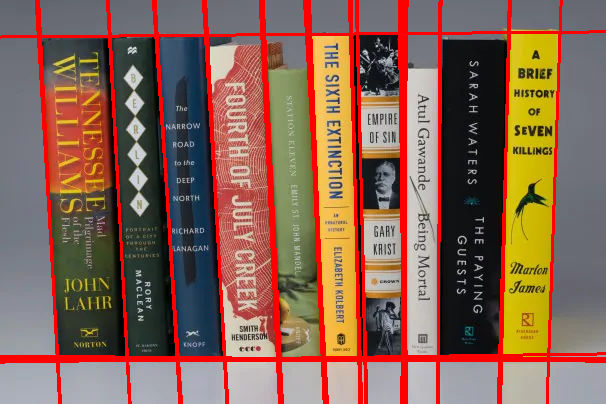

Now we need to split up the books somehow. This is actually quite difficult, but experimentally I have found that the Hough Transform performs reasonably well at this task. The Hough transform works over several different kinds of parametric spaces, but for this example I used it to find lines within the image.

Currently our image, while showing edges, is still just a bunch of pixels. There is no geometric understanding of “shape”. The Hough transform allows us to find parameterized lines within the image giving an understanding of the geometry. Lines are fairly simple as they can be parameterized by \(y = \theta_1 x_1 + \theta_0\). However, to allow for vertical lines we parameterize by \(r = x\cos\theta + y\sin\theta\).

Now for every point in the image \((x_n, y_n)\) we have a function \(r_{x_k,y_k} : [0, 2\pi) \mapsto \mathbb{R}^+\) defined by \(r_{x_n,y_n}(\theta) = x_n\cos\theta + y_n\sin\theta\). Now we define the set \(\mathcal{H}_{x_n, y_n}\)

\[\mathcal{H}_{x_n, y_n} = \{ (x_k, y_k) \mid r_{x_n,y_n}(\theta) = r_{x_k,y_k}(\theta) \land k \ne n \land (x,y) \in Image \}\]\(\mathcal{H}_{x_n, y_n}\) is the set of all points whose curve intersects the curve of \((x_n, y_n)\). Consider the set \(\mathcal{H} = \{\mathcal{H}_{(x_n,y_n)} \mid (x,y) \in Image \}\) of all intersection points. Then we can define lines as

\[Lines = \bigcup_{\substack{h \in \mathcal{H} \\ \land \lvert h \rvert > t}} h\]where \(t\) is some threshold for the number of intersections to qualify as a line. The process for actually computing \(Lines\) looks somewhat different, but still involves finding sets of intersections for every point. The Hough lines for our test book image, pictured below, actually look quite good. There are probably better techniques for segmenting books, but that is left as work for a future date.

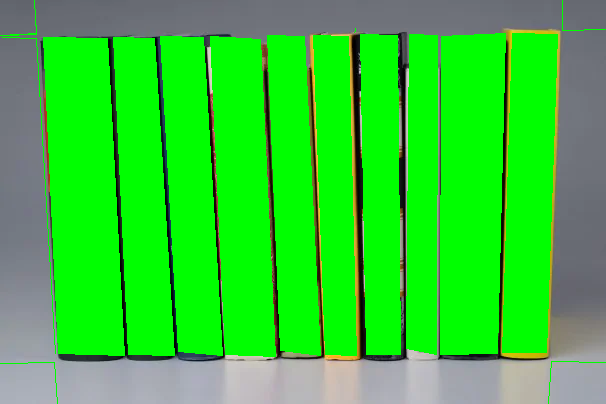

Finally, we have subdivided our books using lines, but we need to “crop” out each book spine for text processing. This can be done by identifying contours within the lines from the Hough transform and masking out each contour region.

To identify contours (geometric shapes within the image) we can use the algorithm by Suzuki, et. al. [2], which is quite complicated, but also conveniently implemented in the open-source project OpenCV. To find the contours I use the Hough lines placed on a white background, so no other image details are identified as contours. Below the contours for our test image are shown in green.

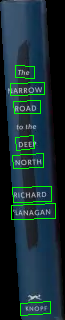

Now for each contour we can mask it on top of the original image to crop out the contents. This will give us a small image for each spine, which we can use for identifying the book. For example, the spine for “The Narrow Road to the Deep North” is shone cropped out in the figure below.

TADA! We have successfully cropped out each book spine in the image.

Judging a Book By Its Spine: Text Detection

The temptation here is to just pipe each image into an OCR algorithm/program and try to get the text. However, as you can notice from our test image: a lot of books have non-standard text alignments. Some have the entire text rotated 90 degrees, while others might have standard text vertically down the spine. We need a way to first identify text within the image and determine its location and orientation.

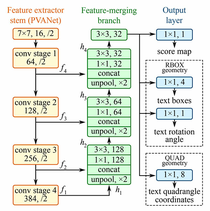

Identifying possible text within a scene is possible with the EAST neural network developed by Zhou, et. al. [3].  EAST is a deep neural network, which can identify and locate probable text within an image. It has its limitations, but it works quite well for our task. Additionally, network inference with this model can be done quite quickly: ~13 FPS as cited by the paper authors. To the right is the EAST network layers as depicted in the paper.

EAST is a deep neural network, which can identify and locate probable text within an image. It has its limitations, but it works quite well for our task. Additionally, network inference with this model can be done quite quickly: ~13 FPS as cited by the paper authors. To the right is the EAST network layers as depicted in the paper.

Once the text has been found we can mask and crop it out like before to feed into an OCR algorithm. I did not delve too far into OCR algorithms, but rather used the LSTM networks in Tesseract OCR for image-to-text. Below is the text found by EAST on “The Narrow Road to the Deep North” spine.

Again, TADA! The OCR pulls out the text [“The”, “Narrow”, “Road”, “Deep”, “North”, “Richard”, “Flanagan”, “Knopf”]. This text, along with the coordinate data, is enough to query a database or google for more information about the book.

Improvements

After some toying around with these computer vision algorithms I believe there are 2 major improvements, which would drastically help the overall accuracy. First, using a different image segmentation algorithm. Segmenting the books using Hough lines works well, but there are much better, more generalizable methods. I looked into RCNN-based approaches, but they all seemed like overkill and they do not work in realtime. More research is needed to find a better segmentation algorithm.

Second, up-scaling the text and using a super-resolution network could help the OCR, which struggled a lot with small font sizes on some books. There has been some recent work by Wang, et. al. on super-resolution scaling for text, which could greatly improve the accuracy of the OCR pipeline stage [4, 5]. Getting this up-and-running, however, seems to be non-trivial.